You can leave home again. Pete Strickland, an American who as a young man served as a Johnny Appleseed of basketball in Ireland, is going back, this time to coach the Irish national team.

“He remains a legendary figure in Irish basketball,” says Bernard O’Byrne, secretary general of Basketball Ireland, the government-funded body that gave Strickland the job. “His appointment is viewed as a coming home.”

Ireland was only Strickland’s home for two years, and that was in the early 1980s, when he played and coached basketball in Cork. Strickland grew up and still lives in the Washington, D.C. area. He’s been a head or assistant coach at U.S. colleges for the last three decades, and was most recently a chief recruiter for Mike Lonergan at George Washington University, a job he left in 2013, before that program blew up.

But, as O’Byrne’s praise indicates, Strickland’s first go-around with basketball in Ireland was as memorable as it was brief. It came at a moment of infatuation with the sport on the island, an infatuation that transcended the bitter divisions along the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The Irish team today recruits its players from both sides.

“Somebody remembered me,” says Strickland. “The job gives me an opportunity to reconnect to the game, which I hadn’t been angling to do. The whole cultural experience of being in Ireland appeals to most people, and it really appeals to me. So I’m getting another chance to do something I think I do well, and, well, it’s going to be fun. I want to get started.”

He’ll get to work next week, as he oversees clinics for coaches and players in Dublin, Galway, and Cork, and will also view the semifinals and finals of the National Cup tournament for scouting purposes.

Among Irish sports fans, basketball isn’t a big deal nowadays. Irish football and hurling (to the unfamiliar, meaning any American, hurling can be described as a melding of lacrosse and kill-the-guy-with-the-ball) remain a huge part of the culture; big matches in the All-Ireland tournaments in each sport routinely drawing sellout crowds of 80,000 to Croke Park in Dublin. European mainstays rugby and soccer are also currently beloved, and Dublin’s Conor McGregor is right now the biggest star in fighting.

Basketball, though, needs a lift. Ireland didn’t even have a men’s national basketball team for the last seven years. Some youth hoop squads have represented Ireland in continental age-group tournaments in recent years, but those teams have been hampered by underfunding and mismanagement, and seem strictly small-time even compared to mid-level American AAU squads. Recently, for example, Basketball Ireland made a cattle-call for the national U20 squad. The announcement said that anybody who showed up with an Irish passport “along with a €10 training fee, packed lunch and water bottle” could try out.

Yet, for a short, weird time when Strickland was a young émigré, Ireland was in love with hoops. Strickland didn’t only witness this affair, but gets credit for helping spark the romance. That’s why he’s “legendary,” as O’Byrne says, and why he got the national team job. Now, at 59 years old, all he’s being asked to do is get the country to care about basketball. Again.

“The people couldn’t get enough basketball.”

Strickland arrived in Ireland late in the summer of 1980. He was 23 years old and pretty sure that he was through with basketball, at least as a player, until shortly before he took the trip.

He’d had a pretty good run. Strickland played high school ball in the mid-1970s, during a golden age of D.C. basketball, at DeMatha Catholic, the prep hoops factory in Hyattsville, Md., that has sent players and coaches to the upper levels of the sport at an amazing rate. (Only Oak Hill Academy, a transfer-dependent talent raider in Virginia, claims to have produced more NBA ballplayers.) DeMatha was coached by Morgan Wootten, likely the most famous high school coach of all time. Among the players at DeMatha during Strickland’s years: Adrian Dantley, a future All-American at Notre Dame, member of the 1976 U.S. Olympic team, first-round NBA pick and a 2008 inductee to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame; Kenny Carr, also a member of the 1976 gold medal-winning Olympic team and first-round NBA pick; Charles “Hawkeye” Whitney, an All-American at N.C. State and first-round pick in the 1980 NBA draft (though Whitney is perhaps most remembered for kidnapping White House counsel, and Hillary Clinton’s Whitewater scandal attorney, Mark Fabiani, in 1996); and current Notre Dame head coach Mike Brey. Strickland says that for a season in the late 1990s, he was one of nine NCAA Division 1 head coaches who had come from Wootten’s high school program.

Strickland’s high school career ended gloriously, with DeMatha facing Dunbar in D.C.’s 1975 city title game. That Dunbar team was so loaded that its two future NBA players (John Duren and Craig Shelton) weren’t even the best players on the squad. Parade All-American and future cautionary tale Stacy Robinson was. “I’ve been around a long time,” Strickland says, “and Stacy Robinson is the best player D.C. ever had.” In front of a raucously pro-Dunbar capacity crowd of 14,500 at the University of Maryland’s Cole Field House, Strickland was the leading scorer in DeMatha’s 67-62 upset of the public school powerhouse.

Strickland went on to Pitt, where he was team captain his last three seasons and left as the school’s all-time assists leader. But he knew he wasn’t NBA material. He put career decisions on hold when his father died in October 1978, at the beginning of his senior college season. After graduation that spring, he went home to help his mother and take care of a younger sister who had a year left in high school.

He got another chance at basketball when he went back to Pittsburgh to play in an alumni game in the spring of 1980. A scout for pro teams overseas happened to be in the stands. He told Strickland after the game that he knew of a squad that could use a guard with his tools, particularly an American. That squad just happened to be in Ireland.

Strickland, like most hoops aficionados, didn’t know a thing about Irish basketball. But at the time of the college alumni game, his sister was about to graduate, and he was looking to stop mourning his father. The scout gave him an exit strategy akin to the plot of John Wayne’s 1952 classic, The Quiet Man, where a young athlete from Pittsburgh heads off to Ireland to move on from some sadness back home. Strickland accepted a deal to play for Neptune, a club in County Cork.

Neptune, established in 1948, played in the Super League, the Irish professional basketball league. The league was founded in 1973 and was never considered one of the top European confederations. The first U.S. players in Ireland showed up to play for Killarney in 1979, when league rules allowed each club to have a maximum of two Americans on the roster. This league was not a stepping stone for players: Basketball Ireland says that Mario Elie, an American who started his professional hoops career with the Killester Basketball Club in 1986 and went on to win championship rings with the Houston Rockets and San Antonio Spurs, is the only player ever to jump from the Super League to the NBA.

For Strickland, however, coming to the Super League ended up being its own reward. Strickland recalls doubting that anybody in all of Ireland (as of 1980, population roughly 3.4 million) would care about his club or his sport when he accepted Neptune’s offer. But when he showed up in Cork, he immediately sensed that he was at the center of a boom waiting to happen.

“The game was on fire, particularly on the northside of Cork, where I lived,” he says. “The people couldn’t get enough basketball. It was like everybody was passing around old Street & Smith yearbooks like they were the Holy Grail. It was weird and amazing.”

Strickland decided to stoke the flames.

“Pete became a missionary, a basketball missionary,” says Kieran Shannon, a columnist with the Irish Examiner and the country’s premier basketball historian.

Shannon was among the Irishmen smitten by the athletic foreigner who’d dropped into town. Shannon was nine years old in September 1981, when he went to Parochial Hall in Gurranabraher to see Neptune play another club from the county, CC Blue Demons. He now compares walking into the local arena to a scene from the Jerry Lee biopic Great Balls of Fire, in which the future rock and roll star enters a blues club for the first time.

“It’s like, ‘My god!’ It was a world you didn’t know existed,” Shannon says of his first Super League game. “That whole era of the 1980s, when guys like Pete started playing here, they were like the pilgrims, just came over and got something started.”

Shannon kept going back to Neptune games, and loved being a part of the overflow crowds that showed up for the Cork derbies over the next several years. Even as a youngster, he was wowed by Strickland’s ballhandling skills, which were completely foreign to the indigenous ballplayers—“He could handle the ball like Hendrix could handle a guitar,” Shannon wrote of Strickland—as well as his command of the game, and his enthusiasm. When Shannon wrote Hanging From the Rafters, a retrospective of the 1980s basketball boom, he devoted a whole chapter just to Strickland. He says the title of the book is a reference to what he witnessed during a typical Neptune/Blue Demons game throughout that decade, where kids were “hanging from the rafters” inside the packed Parochial Hall just to get a view of the action. (We Got Game: The Golden Age of Irish Basketball, a documentary based on Shannon’s book, was released in 2013.)

Strickland made a huge impression off the court, too: The young American joined a Cork theater troupe early into his stay, and volunteered at a bakery just to learn how the Irish make bread. But it was his basketball smarts, imported from the land where the game was invented, that they craved most. And he imparted everything he knew to whoever would listen. The book recalls Strickland’s determination to convert the locals into basketball believers.

“[Strickland] could see that the northside was in the grip of a basketball fever,” Shannon wrote, “and just walking the streets, from school to school, through Shandon and Knocknaheeny, spreading the word and the condition was the honour of a lifetime.”

Shannon illustrates Strickland’s eagerness to teach, and just how alien the game was to the typical Irishman at the time, by recreating a conversation between the imported ballplayer and a nun who invited him to a local parochial school, as he shows up to run what he thinks will be a standard basketball clinic for students.

Pete asks for directions to the school gym.

“Sorry. Meant to tell you we don’t have a gym. But we have this all-purpose room.”

Pete says no problem and is escorted to the all-purpose room.

“This is great,” he says. “I suppose we’ll just roll out the baskets and away we go.”

“Em, sorry. Forgot to tell you, we have no baskets.”

“O-kay. That’s not a problem either, Sister. We can get round that. We’ll just break the girls up in to two lines here and get a basketball for each one.”

“Oh, I’m awfully sorry, Mister Strickland. We thought you were bringing the basketballs.”

And for the next hour he introduced the girls to the joys of defense.

Slides, stance, position. They ate it up. And the next week, when he actually brought some basketballs...! Hallelujah! Another school converted.

Future hoops coaches were also going to school on Strickland. According to Shannon, the talent-evaluation methods Strickland introduced to Irish coaches were revolutionary at the time, and can be found at clinics and camps to this day.

Strickland now says that any drills and jargon he used in Ireland, he’d learned from Morgan Wootten working for several years in his summer camps.

“The people over there were eager and thirsty to learn, and I gave what I had. I was doing it because I liked doing it. I’d learned from a master, and I wanted to give back. And the Irish people liked it.”

Neptune management was also quick to notice Strickland’s teaching prowess. Early into his first season, the club’s head coach was shifted to Neptune’s women’s squad so the men’s job would be open. They asked Strickland if he’d fill it. He was also expected to keep his starting point guard job. There would be no pay raise, however.

“They said, ‘We’ll fly your mother over if you do it,’” he says. “I said sure.”

He’d never been a head coach before. So for Xs and Os and motivational techniques he fell back on everything he’d learned playing for Wootten at DeMatha and Tim Grgurich at Pitt, who went on to a lengthy career as an NBA assistant and teaching guru. (The man known simply as “Grg” is still at it, consulting with the Milwaukee Bucks this season at 74 years old.) With Strickland running the team on the floor and from the bench, Neptune went 18-0 and won the league title, the first undefeated season in club history.

“It was one of those amazing stories,” Shannon says. “Pete brought in a model that everybody could use to develop players, he was a player-coach, and the team goes undefeated. It was all brilliant.”

A very brief history of Irish basketball

The peak and nadir of the Irish national basketball team both came in 1948, when Ireland entered a hoops squad in the Olympics for the first time. According to History Ireland magazine, Ireland only participated in the basketball tournament because the sports world was still in disarray from World War II, and the Games were hosted by nearby London.

Irish athletes had a lousy Olympics overall—the country’s only medal came when Letitia Marion Hamilton, a 69-year old from County Meath, won the bronze in, ahem, painting. (Yes, painting was a medal event up through those games.) But the performance of the Irish basketball squad, making its first Olympic appearance, was a national embarrassment. The team’s roster was made up mostly of soldiers who had no experience playing basketball by the accepted rules of the day. In the years leading up to the Olympics, Irish basketball players had only used a non-round ball akin to a medicine ball, and the version of the game favored by servicemen at the time was contact-friendly to the point of being “closer to an indoor version of Gaelic football than to international basketball,” according to History Ireland.

The Irish hoops team’s humiliation started even before the games began, as players were sent to London without uniforms. The Irish army stepped in and issued non-matching outfits, along with an order to return the garb at the end of the Games. The Irish squad showed immediately that they played worse than they dressed, getting whupped by Mexico, 71-9, in their opening match. The team ended up 0-5, with five blowout losses in which they were outscored 336-82. Ireland was awarded 23rd place in the 23-team tournament, and the Irish national basketball team never appeared in another Olympics.

There’s no way to discern cause from effect here, but since that Olympics debacle, as basketball has grown internationally to the point where it now aspires to challenge even soccer as the world’s favorite sport, Irish athletes have mostly pretended the game didn’t exist, and vice versa. Pat Burke, who was born in Dublin and spent parts of three seasons with the Orlando Magic and Phoenix Suns, is believed to be the only native son of Ireland to ever play an NBA game. Burke was raised in Cleveland from the age of four. (Some Burke profiles don’t even mention Ireland.)

As Strickland knows, though, there was a time ...

“It was the only time I ever felt like a star.”

The immediate turnaround in Neptune’s fortunes when Strickland showed up got Neptune management thinking big heading into the offseason in 1981. They decided Cork was ready to host an international hoops tournament.

Thus began the funniest, most absurd, and—for Strickland’s pals on the hardwood back home—most memorable chapter of his tenure with Irish basketball. The whole story of the inaugural Neptune International Basketball Tournament, scheduled for March 1981 at the Parochial Hall in Cork, seems ripe for cinematic exploitation. Serendipitously, the event got lots of Irish folks to pay attention to basketball like never before. And none of it would have happened without Strickland.

Neptune management had successfully recruited two clubs from Scotland, as well as teams from England and Luxembourg, for their tourney, plus the Irish national squad. Throw in the host club and CC Blue Demons, the local rival, and that meant seven teams had RSVP’d. Technically, that field already met the definition of “international,” so they could have settled on another Irish club to fill out the eight-team field.

But organizers figured few fans would be wowed by fellow countrymen and Euros. Neither would the event’s sponsors, which included Burgerland, the only restaurant in Cork devoted to the ultimate American dish, hamburgers. No, they had to land an American team. And not a squad from a U.S. military outpost in Europe, either. Strickland realized early on that they put him on the tournament’s organizing committee specifically to get a U.S. hoops team to cross the pond.

He tried to get DeMatha, but Wootten declined. “Morgan told me he put it to a vote and the players voted no,” Strickland says with a laugh. “I had my doubts that the players really turned down a trip to Ireland.” Strickland assumes the wise old coach unilaterally decided his talented youngsters wouldn’t get on a plane to face fully-grown foreigners with dubious basketball ability.

Strickland remembers being at a tournament committee meeting as time was running out and no Yanks were onboard.

“Everybody was talking about how they needed Americans,” Strickland says. “I had my head down at the meeting and kind of said under my breath, ‘I guess I could get my buddies.’ And it got quiet and I looked up and everybody was staring at me, going, ‘Really? You can? Really?’”

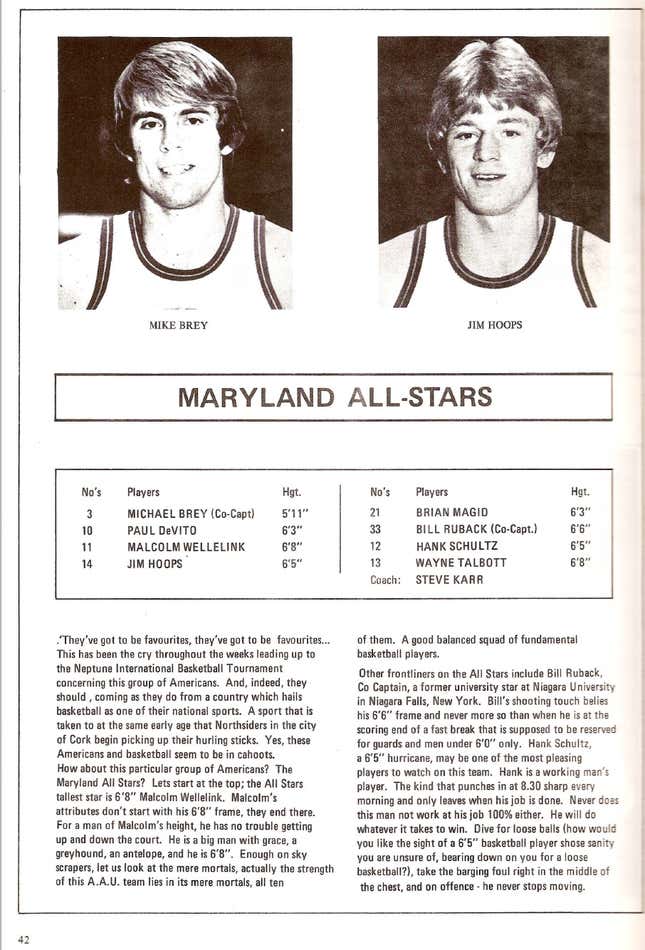

Strickland had the sense that any Americans would do. He could offer open-ended round-trip airline tickets to anybody he wanted. He started making calls back home to basketball buddies, guys who played for or against his DeMatha teams in the ‘70s. Pretty soon a quorum had agreed to come to Cork. The commitments included Bill Ruback, a 6’7” forward who’d played alongside Strickland for DeMatha in that classic 1975 city title upset of Dunbar before going on to a nice career at Niagara University; Paul DeVito, a former Catholic League and playground star who’d dropped out of Jacksonville University and says he gladly quit a $4.19 an hour job with the electric company to accept the free trip to Ireland; Brian Magid, a pure-shooting high school All-American guard who’d played for both Maryland and George Washington and was drafted by the Indiana Pacers a year earlier; and, Mike Brey, another DeMatha alum who had transferred to G.W. and still had a year of college eligibility left. Steve Karr, then a graduate assistant at G.W., was brought along as coach.

In the tournament’s hilariously overwritten official program, which featured photos of John Havilicek and Jerry West on the cover, the U.S. team was billed as the “Maryland All-Stars,” and described as a “running band of Reaganites.” (The Irish were mostly fond of the just-inaugurated 40th U.S. president, who had roots in Tipperary.) The invaders were pegged as the tournament’s obvious “favourites” because “Americans and basketball seem to be in cahoots,” and all Yanks pick up basketballs “at the same early age that Northsiders in the city of Cork begin picking up their hurling sticks.” The program also claimed the squad had “won their respective league two out of the last three seasons.”

That was malarkey, of course. There were no “league titles.” The Maryland All-Stars weren’t even a team before Strickland put them together for the Neptune tourney. Players say the team got its name only because Brey’s father, as a going-away gift, had jerseys made for his son and his son’s mates, and decided “Maryland All-Stars” should be stenciled on the front.

“We met for the first time at the airport,” Magid told me. “We never played [together] before Ireland.”

The Americans landed on St. Patrick’s Day and were whisked from the airport to the holiday parade in Cork, where they found themselves walking with their pal Strickland in front of a crowd they estimate was in the hundreds of thousands. To a man, the All-Stars admit boozing heavily on the plane. (Drinks were free on trans-Atlantic flights back then.) It showed in their parade performance. The way Strickland and Magid remember things, DeVito suffered a back injury when he walked into a float, made up of a backboard and rim set up in the bed of a truck so they could shoot hoops along the parade route. DeVito, however, remembers hurting his back “during practice.” Either way, DeVito, who along with Magid were pegged as the All-Stars’ top shooters, was out for the tournament.

“Paul didn’t mind getting hurt,” Strickland says, “once he found out he could still sit on a bar stool.”

DeVito in no way disputes his friends’ intimations that he didn’t let being knocked out of the lineup spoil his party.

“I should have kept a journal,” DeVito told me. “Then again, I would have had to burn it.”

Not that those who remained mobile enough to suit up for the tournament stayed away from pubs and pints. Guinness was the tournament’s main sponsor, and all the All-Stars took advantage of their benefactor’s free beverages. Apart from the tournament, they played exhibitions, including one against the Galway Democrats, for which every All-Star got a Waterford crystal keepsake. Karr remembers being overwhelmed by the hospitality.

“The Irish people treated us like we were great even though we weren’t,” says Karr. “I was interviewed every day on the news over there. It was the only time I ever felt like a star.”

Karr, who now runs a delivery company that serves the D.C. market, recalls that the All-Stars showed no inclination to end their bender when the actual tournament started. But even with a blood-alcohol level higher than their shooting percentage, the Americans had enough in the tank to whip the green jerseyed Irish national team in the round-robin phase.

Then the Americans took on CC Blue Demons with a spot in the knockout round up for grabs, in front of a packed and intense Parochial Hall crowd. The All-Stars recall that the Cork side, the fans, and their own dubious sobriety weren’t the only things working against them that night. They still swear the refs were rooting for the home team, too. Karr remembers realizing the officials weren’t going to be much help shortly after tipoff when a Blue Demon ran over Magid and a blocking foul was whistled against his player. He went full-blown Bad American. “I yelled, ‘Jesus Christ wouldn’t have made that call!’ with all these priests sitting in the front row,” Karr told me. “I got T’d up right away. That was disrespectful. But I was a kid!”

The game was a back and forth affair from start to finish. The All-Stars were up by two with mere seconds left on the clock when Ruback and Andy Houlihan of the Blue Demons tied up going after a loose ball near the Blue Demons basket. A jump ball was called. And, say the All-Stars, the officials made sure the Blue Demons had more than the luck of the Irish on their side.

“The ref tossed the ball so far to the other guy’s side, there was no way I could even reach it without knocking [Houlihan] over,” Ruback says. “I had no chance.”

Houlihan tipped the ref’s allegedly slanted lob to a Demons teammate, John Cooney, who launched a three-pointer at the buzzer. Cooney’s shot went in. The crowd went ape. The Yanks were booted out of the tournament.

“Pete says the guy who hit the shot on us still drinks for free,” Brey says, “because the people in Cork thought they beat Team USA.”

Problems with the refs notwithstanding, the All-Stars ended up okay with their elimination. “That gave everybody more time to drink,” says Strickland.

Strickland played for his regular club, Neptune, in the tourney, and also got eliminated before the semis. It didn’t much matter that Neptune got beat, but he figured management would be mad at the world, and mostly him, that the Maryland All-Stars lost. The Americans went in as the fan favorites and main attraction, and nobody was counting on them being eliminated.

“They’re going, ‘Pete, you told us these guys were good! What happened?’” Strickland says. “They figured nobody was going to show up for the next games with the big draw knocked out.” But to the amazement and relief of Strickland and the Neptune bosses, having Cooney, a homegrown hero, and his local mates vanquish the foreign invaders in such dramatic fashion turned out to be the greatest possible outcome, both for the promoters and basketball in Ireland. The win legitimized the quality of Irish hoops to the townspeople. Parochial Hall was oversold for the next two rounds, even without the Americans.

After the success of the tournament, Burgerland signed on as Neptune’s top sponsor, and the team was henceforth known as Burgerland Neptune. The club made enough money in a lousy national economy to build what was called the first team-owned basketball arena in Europe—Neptune Stadium—which opened on Jan. 1, 1985. The tournament was also a boon for the crosstown rivals. A season after Cooney’s big shot, Blue Demons became the first Super League team with a national sponsor, the soft-drink Britvic. Cork derbies drew rafter-hanging crowds for the next several years.

The Blue Demons’ defeat of the Yanks was treated as a big deal nationally. A photo of Cooney taking the winning shot made the cover of Basketball Ireland magazine, the country’s primary hoops periodical. And higher-caliber American college players quickly started considering Irish basketball, including Mario Elie, who in 1985 began his pro career with Killester, a Dublin-based team in the Super League.

Cooney, now 61 years old, still lives in Cork. He confirms Strickland’s assertion that being a hero that night in 1981 served him well in pubs. “I got plenty of free pints of Guinness for that shot,” he tells me.

He pooh-poohs the All-Stars’ assertion that the refs worked against the guests. “There was no home cooking,” he says, “just they were beaten by a better team on the day and a shot that was part of the magic of Irish basketball at that time.”

Shannon’s epitaph for inaugural Neptune International Basketball Tournament: “Even when Pete got it wrong, he got it right.”

The boom was on.

“This wasn’t me trying to recapture anything or get something back ... That’s just not me.”

Strickland, alas, wasn’t around to enjoy much of the Irish basketball heyday. His relationship with Neptune management soured during his second season there. Team officials revoked the power they’d given him to make personnel decisions, including what Americans to bring over. Burgerland pressured the team to use up their American slots on high-flying dunkers rather than guards like Strickland.

Race was also a factor. In Shannon’s book, Burgerland marketer Jackie Solan, who joined Neptune’s board of directors after the tournament, admits telling club management, “I want a couple of black fellas that can dunk the bloody thing.” Strickland, who remembers Solan as “the Dan Snyder of Ireland,” was told to rescind an offer he’d made to Dan Harwood, a white Yank also from the D.C. area who captained Rick Pitino’s first squad at Boston University. Strickland says he understood the commercial interests at play: “Irish fans were attracted to black players because they hadn’t seen them,” he says. “They’d seen plenty of white players.” But he couldn’t go back on his word to Harwood. And when management wouldn’t relent, he packed his bags and went home after only two seasons. According to Shannon, most of the Neptune players and even members of management cried when Strickland told them he was leaving.

Neptune went on to win seven Super League titles through 1991, and Shannon attributes the success to the foundation laid by Strickland and the excitement he created for the club and sport. (Neptune’s star player during this heyday was Terry Strickland, an African-American player not related to Pete Strickland.) Shannon also says Strickland’s teaching methods, which he shared at clinics that he periodically hosted in Ireland for several years after leaving Neptune, became the national standard for Irish coaches. “Strickland had offered a template,” Shannon said, “which every leading basketball camp in the country would use for generations.”

Strickland came back to the U.S. in 1982. He married an Irish-American girl, and, after a few seasons helping Wootten at DeMatha, began his long college coaching career, highlighted by his seven-year stint as head coach at Coastal Carolina, where he was named the Big South Conference’s coach of the year in 2000. Through the years he also had assistant jobs at Virginia Military Institute, Old Dominion, Dayton, North Carolina State (under fellow DeMatha grad and Wolfpack head coach Sidney Lowe) and, finally, George Washington. At this last stop, he was known as one of Mike Lonergan’s top recruiters before jumping off just before the 2013-14 season started, citing a desire to watch his son, then a junior playing for Salisbury University, finish up his college career. (Lonergan was fired by the school this fall after the Washington Post reported that players were leaving the program in droves and that many Colonials insiders could no longer take the head coach’s “bizarre and abusive” behavior.)

Since leaving G.W., Strickland has been giving motivational speeches, doing sports-media work (he was most recently a member of the production crew for the December 27 Military Bowl in Annapolis), and emotionally preparing for a life after basketball. After he watched “every dribble” of his son’s final two seasons at Salisbury—he graduated in 2015—Strickland found himself in a situation not too different from his days after leaving Pitt, when he’d helped his sister finish school and accepted he was done with basketball.

Yet just as Strickland was about to close a basketball chapter, Ireland beckoned all over again.

Strickland says he’d stayed in touch with Super League acquaintances through the years. But he was nevertheless shocked when Francis O’Sullivan, who was a teenager playing with Neptune when Strickland arrived in 1980 and has been his friend ever since, called this fall. O’Sullivan said Strickland’s name was coming up in conversations about coaching the recently resurrected national team. The rumors turned into a job offer in November. And he took it.

“Last year, after my son finished, was the first year I was not in the gym almost every night in a long time,” he says. “So, sure, the itch was there. This job was a way to fill that void a little bit, and not in a sad, or wanting way. I had nothing but good times in Ireland, and made lifelong friends there, and, sure, that was when I was young. But this wasn’t me trying to recapture anything or get something back in some forlorn way. That’s just not me.”

He knows what he’s getting into. The popularity of basketball in Ireland isn’t far from where it was during Strickland’s first go-round there. The Super League boom of the 1980s began cresting when a few owners decided they didn’t like American players getting most of the attention and money, and to appease this tightwad/xenophobic faction, Basketball Ireland reduced the maximum number of Americans allowed per club from two to one beginning with the 1988 season.

For all the seeds planted by Strickland and the other early American arrivals to the Super League—the folks Shannon calls “pilgrims”— there wasn’t enough homegrown talent to make up for skills deficit. Interest in the sport among Irish sports fans began waning as soon as the Yanks went away, and continued to fall. Irish basketball hit bottom after the national economy of the so-called Celtic Tiger collapsed late in the last decade.

For Shannon, the low point came when he attended the 2009 national club playoffs and was crushed by the utter indifference of his countrymen. “Everywhere you … looked there were empty seats,” he wrote. “For the first time in quarter of a century there were no TV cameras for a men’s semi-final. I was never so despondent about Irish basketball.”

Neptune, historically the most celebrated and decorated club in Irish basketball history, decided last season to drop out of the Super League, citing disinterest and financial reasons. Burgerland quit sponsoring the club in the early 1990s. Neptune now fields a second-division squad, but it’s plainly a half-hearted effort: The club’s website gives almost as much play to the weekly bingo night at the Parochial Hall as it does any basketball endeavors.

The indifference that has plagued the Super League trickled down to the Irish national squads. The men’s team had been foundering for years amid apathy and debt before it was completely disbanded in 2009 by Basketball Ireland. Players were expected to pick up the costs of playing for their country, and coaches were asked to work pro bono. An attempt to revive the senior national team in 2013 was quashed by FIBA, the Switzerland-based sanctioning body for international basketball, because Basketball Ireland still owed the group money.

Some age-group national teams stuck around, but extreme mismanagement ruled the roost. A representative tale: In 2013, the Irish national U18 team entered an international tournament in Cherbourg, France that was to be its return to international competition after a long suspension because of the FIBA debt. The Irish lads upset squads from England, Switzerland, and host France to make the finals, some rare good news from an Irish basketball squad. But after qualifying for the championship, the players were told managers had booked a ferry home to Ireland that would depart at the same time as the title game was scheduled to tip off. They didn’t miss the boat. They missed the game.

But O’Byrne, a former executive with Coca-Cola, was recruited by Basketball Ireland for his business experience. He balanced the books enough to get FIBA to clear Ireland for international competition in 2016. And he had enough money left over to pay for a coach for the senior team. (Strickland declined to divulge his salary, but says that while he’s hardly a volunteer, he won’t be “buying a villa in France” with his Basketball Ireland windfall.) There’s no Olympics bid on the horizon. But players on national team will have matching green uniforms, won’t have to practice with medicine balls, and won’t have to worry about missing games because they have to catch a boat.

“The innocence is gone. The world is smaller.”

The trends are not all bleak as Strickland takes over the national team. The Irish economy, which much like the national squad has been weak for most of the last century, is now among the strongest in Europe, with investments from U.S. companies getting a good share of the credit for the bullish outlook. And Shannon says he’s noticed Irish kids paying a bit more attention to basketball of late, mostly the American variety. “The innocence is gone. The world is smaller. We’re just not wowed like we were [in the 1980s],” he says. “But the kids here think the NBA is cool and know who Kevin Durant and LeBron James are.” Participation in girls basketball has suddenly gotten very strong in Irish schools, too. Shannon attributes some of the increase in hoops interest among Ireland’s youth to a domestic role model: Kieran Donaghy, 33, a national hero for his exploits in Gaelic football, became a sort of Irish Bo Jackson late in life by playing for a basketball team from his native Tralee in a national tournament earlier this year. The hardcourt foray from the former Footballer of the Year award winner, who has told interviewers that as a boy he “dreamt of making the NBA, not All-Irelands,” led to Tralee getting a new club in the Super League, seven years after the town’s last league franchise folded. And the Tralee Sports Complex has been packed in the inaugural season. (Now if only Conor McGregor would give hoops a shot between bouts.)

Since his hiring, Strickland has been watching video of Irish youth squads and professional clubs on his computer. For the short-term, Strickland’s team-building exercises are geared toward the FIBA European Championship for Small Countries, which will be held in 2018 in San Marino. His appointment by Basketball Ireland as head coach of the national team expires after that tournament. “I hope we draw some new, really small nations that aren’t even nations yet,” Strickland says, laughing.

Strickland will allow Americans with Irish passports to try out, but says he wasn’t hired to create the “Dream Team of Ireland.” He knows he needs natives for the long-term health of the squad.

“[Basketball Ireland doesn’t] have those kinds of illusions, and neither do I,” he says. “But we want to make this a team that kids will grow up wanting to be on.”

There’s no plan to shoot for a return to the Olympics, though he says he might come up with a rallying cry based on the country’s unfortunate last appearance in the games: “Something like, `Remember ’48!’ might fire people up,” he says.

Strickland has gotten lots of kudos from longtime pals in the U.S. and Ireland. Shannon called the hiring “inspired.” Brey was also among the first to congratulate his high school chum on getting the new gig.

“He has the perfect personality to build their national program,” he says. “They need an energy guy, and Pete has it in boatloads.”

Brey paid a hefty price for his first trip to Ireland: When he returned to America following the 1981 junket to Cork, the NCAA suspended him for the first three games of GW’s 1981-82 season for playing against pro teams overseas. The Neptune International tourney went away in 1989. But, suspension be damned, Brey has such good memories of that trip and the hijinks around the tourney that if Strickland gets another international hoops summit together, he’d be willing to serve as a basketball ambassador all over again. And he knows some old American guys who’d serve with him.

“The more I think of it,” Brey says, “the more I think the Maryland All-Stars should come back together.” (The All-Stars, after all, are 1-0 against Ireland’s national team, lifetime.)

Strickland expects to fill out his coaching staff this month, too. Strickland says some longtime American pals have hinted they’d consider coaching in Ireland. Brey is too busy coaching another group of Irish to really mean it. But Karr, who as coach of the Maryland All-Stars back in 1981 has a 1-0 lifetime record against the Irish national team, really means it. “Tell [Strickland] if he needs a coach in Ireland, I’ll do it,” Karr tells me. “I’m dead serious. That Ireland trip was the highlight of my life. Tell him that. I’ll do it!”

But, grateful as Strickland is that his pals came over all those years ago, he’s not bringing them back. This time around, Americans can only do so much for Irish basketball.

“I’ve got to hire some Irish guys,” he says.