In the year 2000, it looked like a bright new day for abortion rights.

The FDA was set to approve the first medication specifically designed for terminating a pregnancy: The “French abortion pill,” as it was called—the name, a nod to the drug’s origins, also happened to convey a whiff of the laissez-faire—was about to come to America.

Abortion rights groups had been fighting to make the drug available in the U.S. since the 1980s, when it was first developed. More than a dozen countries had approved the pill, and more than 500,000 patients had taken it in Europe alone.

For patients in the U.S., gaining widespread access to the drug would mark a “historical moment”—one “comparable to the arrival of the birth control pill 40 years ago,” said the then-president of Planned Parenthood. A Seattle doctor who participated in the drug’s clinical trials predicted in January 2000 that women would eventually be able to receive the pill from their family physicians, sidestepping the need to visit an abortion clinic. “It will mainstream abortion into regular medical care,” she told the Chicago Tribune.

Nearly 22 years later, the U.S. abortion rate has steadily fallen, and more than half of abortion patients now get medication instead of undergoing in-clinic procedures. But while the pill has made abortion safer, easier, and more private for millions of patients, political opposition has kept it from fulfilling its initial promise. In addition to strict FDA regulations, dozens of states have placed limits on who can administer the medication and how patients can receive it. It never reached the medical mainstream.

And yet, as Republican-led states pass extreme bans on abortion and the Supreme Court prepares to end the protections of Roe v. Wade, abortion medication stands to become the primary tool to mitigate the damage of the health crisis to come. Insofar as the post-Roe era will look different than what preceded the 1973 ruling, it will be in large part because of this decades-old technology, which puts agency into the patient’s own hands.

How It Works

A medication abortion involves a two-drug regimen. The term abortion pill typically refers to the first drug, mifepristone, because it was specifically designed and approved for that purpose. (Those who read the news in the 1990s may recall its original name, RU-486, a reference to its manufacturer.) The second drug, misoprostol, was developed in the 1970s to treat stomach ulcers. It’s also used to induce labor and stop postpartum hemorrhaging.

When a pregnant patient swallows a tablet of mifepristone, the drug inhibits her body’s supply of progesterone, a vital hormone for a growing pregnancy. Without the support of progesterone, the patient’s uterine lining begins to break down. A day or two later, she takes misoprostol, which causes the uterus to contract and empty, leading to cramps and bleeding akin to an extremely heavy period.

Before the pill was available in France, where it was created, a patient’s only option was a suction abortion, an in-clinic procedure that empties the uterus. (This is still standard procedure for first-trimester abortions that aren’t treated with the pill. Later in pregnancy, a doctor may also use tools to remove the contents of the uterus.) Providers usually wouldn’t perform suction abortions before the eighth week of pregnancy because the fetal tissue was barely visible at that point, making it difficult for a clinician see if an abortion was successful. The pill allowed women to get abortions earlier, rather than enduring weeks of unwanted pregnancy symptoms.

Naturally, there was plenty of political and religious pushback. Just a month after the pill’s debut in France, its manufacturer suspended distribution, citing pressure from the Catholic Church and anti-abortion groups. The French health minister ordered the company to resume selling the drug, which he praised in poetic terms. It was nothing short of the “moral property of women,” he said.

What It Changed

That the pill skewed the average abortion earlier in pregnancy was in some ways an unwelcome development for anti-abortion activists, who feared it could make the issue a less effective political rallying point. The earlier women could get an abortion, the clearer it would be to them that what was happening was a normal biological process. They would see the pregnancy expelled—a chance they’d never get in a clinic—and all they would see is clots and blood.

In short, medication abortion would demystify a procedure that had been shrouded in secrecy and shame. As one leader of the reproductive rights movement put it in 1994, patients would “say, ‘Is this it? Is this what it’s all about? It’s not about killing a baby.’ ”

In fact, a pregnancy ended through induced uterine contractions was so dissimilar to the public conception of an in-clinic abortion that reporters, patients, and even some doctors had trouble putting the two treatments in the same category. Newspaper reports explained that the pill worked by “causing a miscarriage.” A doctor researching mifepristone in the 1980s said the drug would prove useful “as a menses inducer for women who are late with their periods.” A 1999 article in Family Planning Perspectives told of patients who didn’t believe the pill counted as a “real” abortion, given that “it seems to induce a miscarriage.” (The article stressed that clinicians must fully explain the function of the pill, such that the patient’s consent is freely given.)

Opponents of abortion rights knew they had a lot to lose to a drug that lent an air of absurdity to the images they held outside clinic doors of mangled fetal tissue and rosy-cheeked infants. When the pill was approved in France in 1988, the Washington Post reported that anti-abortion groups warned of the “banalization” of abortion that could follow. One Republican pollster told a reporter that the drug risked making pregnancy “a problem that can be easily taken care of.”

So the political right launched a multipronged effort to ensure that unwanted pregnancy remained stressful and hard to manage. Anti-abortion groups threatened to organize boycotts of any businesses that marketed mifepristone in the U.S. And while George H.W. Bush was president, the FDA prohibited patients from importing the pill from other countries, even though it allowed Americans to bring in other unapproved medications from overseas—including experimental AIDS medications and snake oil drugs like Laetrile. (The Supreme Court upheld that ban before President Bill Clinton reversed it, after which pregnant women of means began flying across the Atlantic to obtain mifepristone from London.)

Drug trials stretching back to the 1980s had shown mifepristone to be 90 percent effective up to 10 weeks of pregnancy—and even more effective in earlier weeks—but in 2000, the FDA only approved its use in the first six weeks.

In the two decades that followed, mifepristone remained outside the domain of mainstream medical care because of structural hassles the FDA put in place. The agency compelled patients to obtain the pills directly from a medical provider rather than a pharmacy, and doctors who administered the pill had to be specially certified.

So by the anniversary of the pill’s FDA approval, only 6 percent of gynecologists and 1 percent of general practice physicians had actually provided it, despite the fact that, in a survey conducted two years before mifepristone became available in the U.S., more than 54 percent of OB-GYNs expressed interest in offering the drug to patients who wanted it.

But access to the pill slowly expanded. In 2016, the FDA updated the drug’s label to allow nurse practitioners and physician assistants (rather than just doctors) to administer the medication and to let patients attend their post-abortion follow-up appointments by phone, theoretically reducing their mandatory visits to a clinic from two to one.

The agency also extended patient eligibility from six weeks to 10 weeks of pregnancy, bringing its official recommendation in line with the way many abortion providers had already been prescribing the drug. Under the drug’s original label, only about 37 percent of U.S. abortions were eligible for the pill. With the new protocol, about 75 percent of abortions could be performed with medication.

Post-Roe Possibilities

Conservative lawmakers have done their best to keep abortion patients away from the pill. Despite the FDA’s new rules, 32 states still limit the ability to administer mifepristone to physicians, and in 19 states, the clinician must be physically present to give the patient the drugs. (That restriction is a response to programs developed to serve rural areas, in which a patient can consult with a physician on a video call to get abortion medication.)

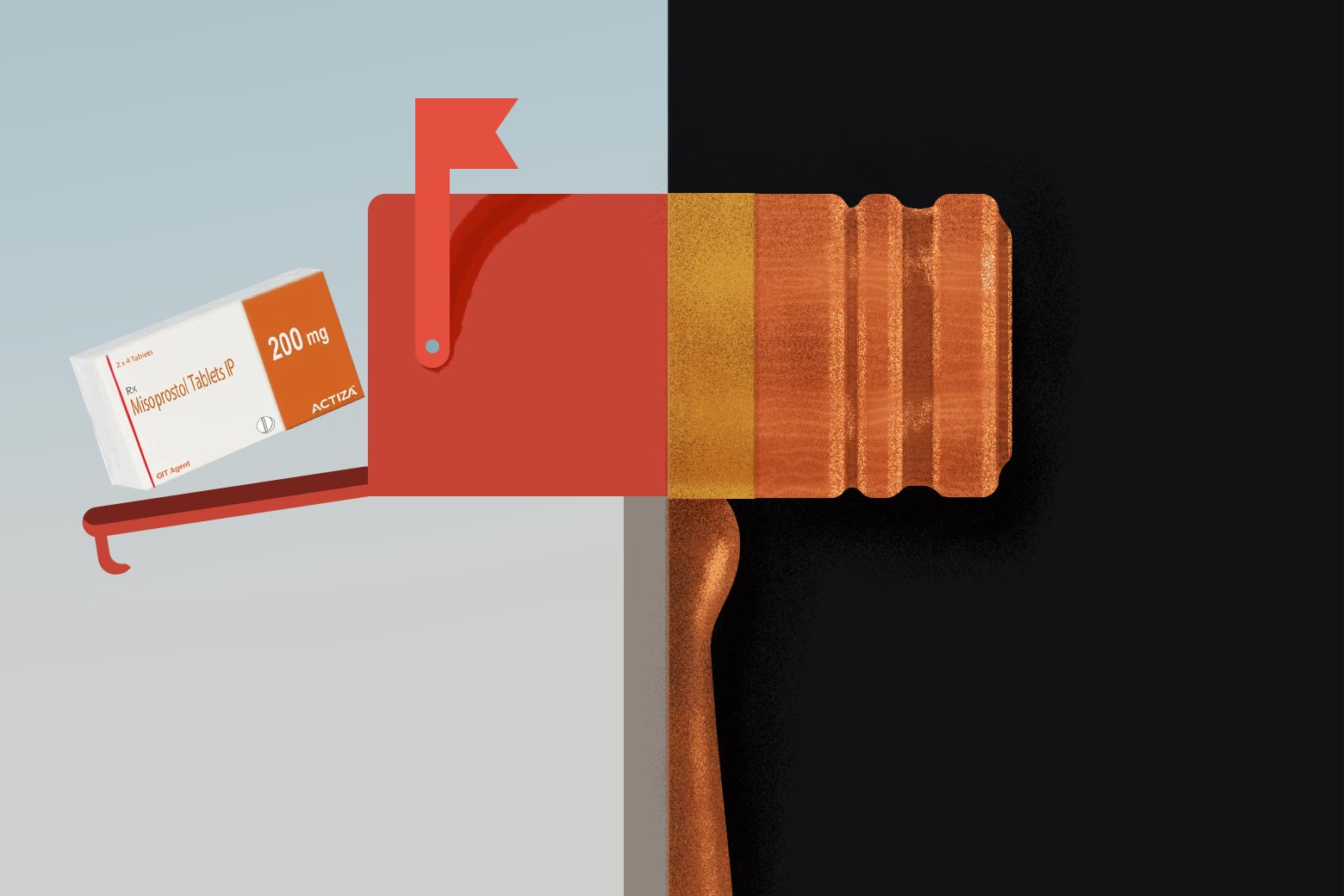

But for the first time in history, in 2020, the majority of U.S. abortions were performed via medication. And just last year, the FDA made a monumental move that could prove critical to abortion access after Roe is overturned: It ended the in-person requirement for getting the pill. Now, mifepristone can be prescribed by telemedicine and sent by mail.

States that are hostile to abortion rights have already banned the use of telemedicine for pregnancy termination. But by loosening restrictions on the abortion pill, the FDA has publicly affirmed what decades of research and hundreds of thousands of patients’ worth of data has shown: Medication abortion is safe. It’s an effective way to end a pregnancy. Most importantly, it’s a medical intervention the average patient is well equipped to manage on her own, without extensive guidance or intrusion from health care providers or the state.

Anti-abortion groups have accused the government of allowing “dangerous at-home, do-it-yourself abortions” by ending regulations “designed to protect women from serious health risks and potential abuse.” But with telehealth medicine, the abortion pill’s safety and efficacy numbers have remained high. When the FDA allowed a research program to try sending pills by mail beginning in 2016, it found that 95 percent of the abortions were successful without any in-person appointments.

A recent study of more than 52,000 abortion patients in England found that patients who did their initial consultations via telemedicine had comparable outcomes to those of a cohort that was required to have in-person consultations and ultrasounds. In both groups, more than 98 percent of patients had successful abortions and less than 0.05 percent experienced serious adverse events.

This is unsurprising but nonetheless heartening news for abortion rights advocates planning for the end of Roe. Terminating a pregnancy outside the legal medical establishment previously involved travel, a trained provider, a hidden place, a well-coordinated time, and some physical risk. But the future of illegal abortions isn’t coat hangers. It’s medication.

The Mail-Order Marketplace

Today, numerous websites provide information on acquiring abortion pills through the mail. Plan C links to online pharmacies that ship the drugs from overseas and explains how to use telehealth appointments and mail-forwarding services to get pills from states with looser restrictions. Doctors at Aid Access, a European initiative that helps people access abortion medication from places where it can be expensive or difficult to obtain, write prescriptions that are filled through a pharmacy in India. The organization has also begun serving people who aren’t yet pregnant but want to be prepared with a set of pills for a possible unplanned pregnancy. The FDA sent Aid Access a cease-and-desist letter in 2019, ordering it to stop selling unapproved brands of mifepristone and misoprostol to U.S. patients. The founder, Rebecca Gomperts, maintains that since she is not selling the medication—only referring patients to an independent pharmacy—she is not breaking the law.

Mail-order treatment won’t solve the problem of abortion access in the U.S. after Roe is overturned. A lack of information, money, internet access, or a safe home environment could prevent someone from ordering pills online. More invasive abortion procedures may be necessary for people who are more than 10 weeks pregnant. (In some places, such as Great Britain, medication abortions are provided until 24 weeks of pregnancy, but usually under clinical supervision.) No matter how deeply abortion rights advocates invest in clandestine delivery networks and digital security, people may be prosecuted for importing abortion pills on behalf of others or smuggling them across state lines. Patients may be put on trial for ingesting the pills, too—as will those seeking care for pregnancy complications, because, to a health care provider, a medication abortion in progress is indistinguishable from a miscarriage.

But at a moment when women’s bodies and lives are about to become less their own than they were a half-century ago, the abortion pill will be more essential to American self-determination than it ever was when abortion was legal in all 50 states.

In the anticipatory years before the abortion pill came to the U.S., it wasn’t just the prospect of earlier abortions and easier distribution that excited women’s health advocates. It was the chance to give patients a sense of autonomy over their own bodies—exactly what they will lose when the Supreme Court allows states to assume dominion over their reproduction. It is wrenching, now, to read what one of the doctors involved in the mifepristone trials told a Baltimore Sun reporter in 1996 of how her patients responded to the drug. “They felt more in control,” said the doctor, a medical director at Planned Parenthood. “They said they felt it wasn’t something that was done to them; it’s something they chose to do. They’d say, ‘I did it.’ Those were the words they used.”