Between 1947 and 2005, the US evangelist Billy Graham, who has died aged 99, conducted more than 400 crusades around the world, preaching to millions of people. He was one of the first western Christian leaders to speak beyond the iron curtain, first in Hungary, then in Poland and Russia. In 1973, more than a million people attended the closing ceremony of his crusade in Seoul, South Korea. He gained access, with great difficulty, to China in 1988 and North Korea four years later.

Like thousands of others in the UK, I first heard Graham at Earls Court stadium in 1966, on one of his London crusades. Though fewer had turned up than to Harringay stadium in 1954 (when he ministered to more than 1.3 million people in three months), the numbers were impressive. The glamour of expensive and skilful hype, lighting and music, and support from local religious leaders, drew the crowds.

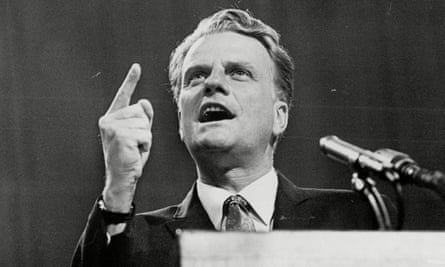

Graham was handsome and eloquent, but his proclamations were strident, and his theme – “what would happen to you if you died on your way home?” – spoke of an unbelievably hardline deity. His favourite text then, and throughout his world tours, remained: “God so loved the world that He gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in Him should not perish but have everlasting life.” There was little place for a questioning faith or political action, but he had the ring of someone who was totally sincere.

He was gentler, more humane and more diplomatic than the west coast evangelical leaders who succeeded him in the US. Graham respected the sharp protests against materialism in the 1960s and student cynicism about the political process, especially during the Vietnam war. But he did not personally question that war, owing to his conviction that “godless communism must be defeated”. While it was fair enough for Graham to reply to a bearded student at Miami in 1969 who asked him to pray for “good friends and good weed”, “You can also get high on Jesus”, it was noticed that he never grappled with the liberation theology of Hispanic America.

He preached strongly that “Jesus was a nonconformist” but found it hard to criticise the cold war anti-liberation ideology of the establishment. He met the Sorbonne student leaders of 1968 in the US embassy in Paris, but could not share their longing for a new order and urged personal conversion as the answer to their problems.

In 1996, when he was presented with the US Congressional Gold Medal, he spoke of wondering whether the 21st century would be as bloody and tragic as its predecessor. “Our basic problems come from the human heart,” he said.

Eldest of four children of Morrow (nee Coffey) and William Franklin Graham Sr, he was born on a dairy farm outside Charlotte, North Carolina, then a poor, hard-pressed rural area. His family were strict Presbyterians, rigorous and righteous. They lost their savings in a bank collapse during the Depression. Childhood treats for Billy were being given a calf to raise and take to market, having a home-made crystal radio receiver and driving a goat cart.

His religious upbringing was strict. At 16 he went forward to commit himself at a Southern Baptist mission and later spoke in a jail about his experience of conversion. Part-time work as a brush salesman led him to try to give “a hard sell about Christ, as much as about Fuller’s brushes”. He studied at a series of evangelical colleges, including Wheaton College, Illinois, where he met Ruth McCue Bell, whom he married in 1943. In 1944, he became a full-time evangelist for the American Youth for Christ campaign. The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, from which he drew a modest salary, was set up in 1950 (and is now headed by his son, Franklin).

He was now a well known evangelist, but his rural background remained one of his great strengths. As a child, he had mixed with black workers on his father’s farm and on a crusade at Chattanooga in 1953, he removed the customary ropes that separated white people from black people – the white head usher at the crusade resigned. Martin Luther King respected Graham’s role: “You stay in the stadiums, Billy, because you will have far more impact on the white establishment than if you march in the streets.” Graham refused to visit South Africa until apartheid regulations were lifted from his meetings, and said: “Christianity is not a white man’s religion … Christ belongs to all people.”

Crusade succeeded crusade, each involving meticulous organisation, massive fundraising and diplomatic briefings. After initial gaffes when he betrayed some of President Harry S Truman’s and President Richard Nixon’s remarks, he was meticulously briefed before meeting celebrities. In 2002, he apologised when the Nixon tapes revealed they had both been guilty of antisemitic comments.

Graham was always traditionalist and conservative. The radicalism of martyrs of his time – Archbishop Oscar Romero, King or Jonathan Daniels (the Episcopalian seminarian shot down in Alabama) – did not win his support. He would rarely invite world Christian leaders to state non-evangelical views from the platform at his crusades, and Graham’s converts were not guided towards a more generous, open understanding of Christianity, catholic, ecumenical and reasonable, as well as reformed. As the world became one village, Graham could have done more to help the church to become a tolerant, open and caring community.

Anglican archbishops were often asked how they felt about Graham, who preached to much larger crowds than they. Michael Ramsey said: “He may do some good, but I feel that his mission could show a greater awareness of the political and intellectual circumstances in which we are placed at the present time.” Robert Runcie was more friendly, and Graham went to Runcie’s enthronement in Canterbury in 1980, as he did to George Carey’s in 1991.

Runcie and Graham also got to know each other on ecumenical journeys in eastern Europe and Russia. Graham irritated some who heard him speak in Guildhall after receiving the Templeton Prize in 1982, when he implied that there was more religious freedom in Russia than there was in England because England had an established church – a view refuted by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn the following year. For a time he helped to finance the evangelical journal The Church of England Newspaper. Graham’s autobiography, Just As I Am (1997), makes much of the occasions when he met the Queen and the Queen Mother.

He advised US presidents from Truman to Obama. Watergate memoirs revealed his bitter-sweet relationship with Nixon, who told a trusting Graham that “he believed the Bible from end to end”. To Graham, “Watergate was a brief parenthesis” and he seemed more worried by Nixon’s language than by his dishonesty. But when Ronald Reagan asked him for an endorsement in 1980, Graham said: “Ron, I can’t do that. I think it would hurt us both.”

He gave private advice on the religious passages in presidential speeches and offered his prayers at times of crisis, especially for George HW Bush at the declaration of the Gulf war and Bill Clinton at the Oklahoma bombing. Even from his early days, Graham cast a spell over world leaders. In 1954 Winston Churchill, talking about life after death, had trusted Graham enough to confess: “I am a man without hope.”

Graham’s optimistic warmth, his astonishing energy and total assurance that God is, and loves this world, won him committed supporters. For decades he received more than 10,000 letters a week, often with small donations and promises of support. In his years of retirement and illness, he remained widely respected. Many were delighted when he was invited to the British embassy in Washington in 2001 for the ambassador, on behalf of the Queen, to award him an honorary knighthood. His simple vision of the Christian gospel and his absolute conviction of the truth of Christianity remained among the positive religious memories of many millions.

His wife, Ruth, died in 2007; he is survived by their three daughters, Virginia, Anne and Ruth, and two sons, Franklin and Ned.

William Franklin Graham, evangelist, born 7 November 1918; died 21 February 2018